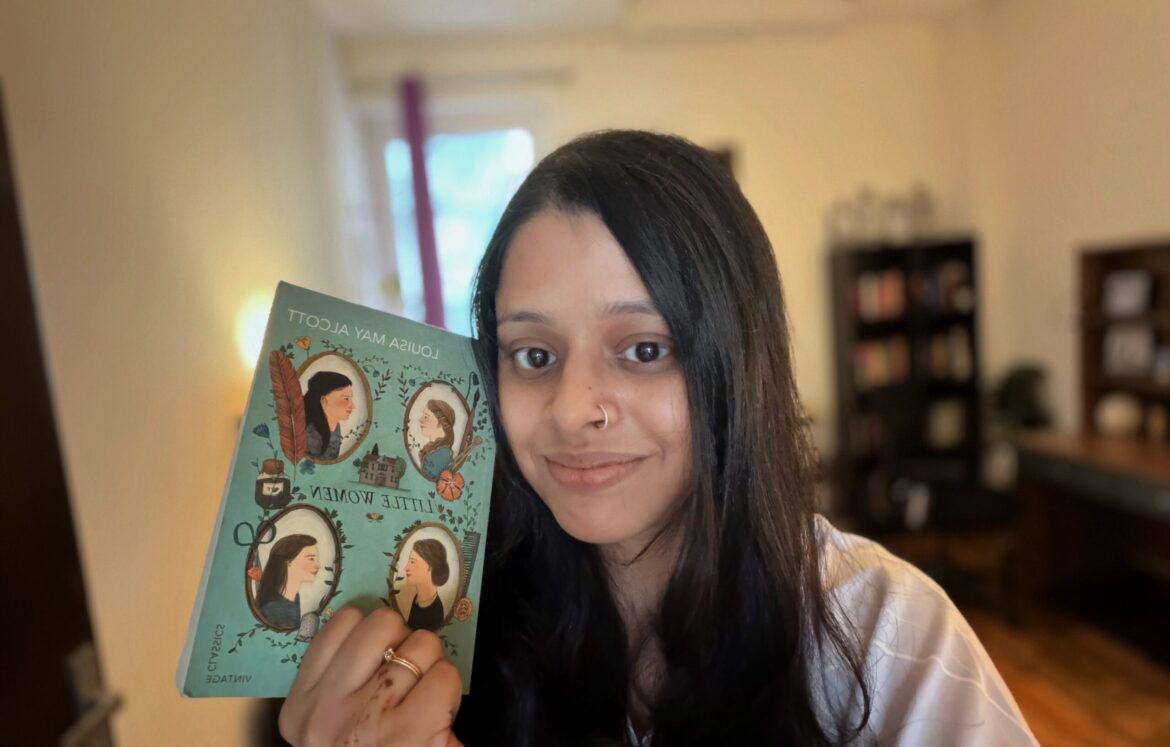

Of Sisters, Stories, and Selfhood: Reading Little Women Anew

- by Namrata Das Adhikary

- October 13, 2025

- 0

- 290

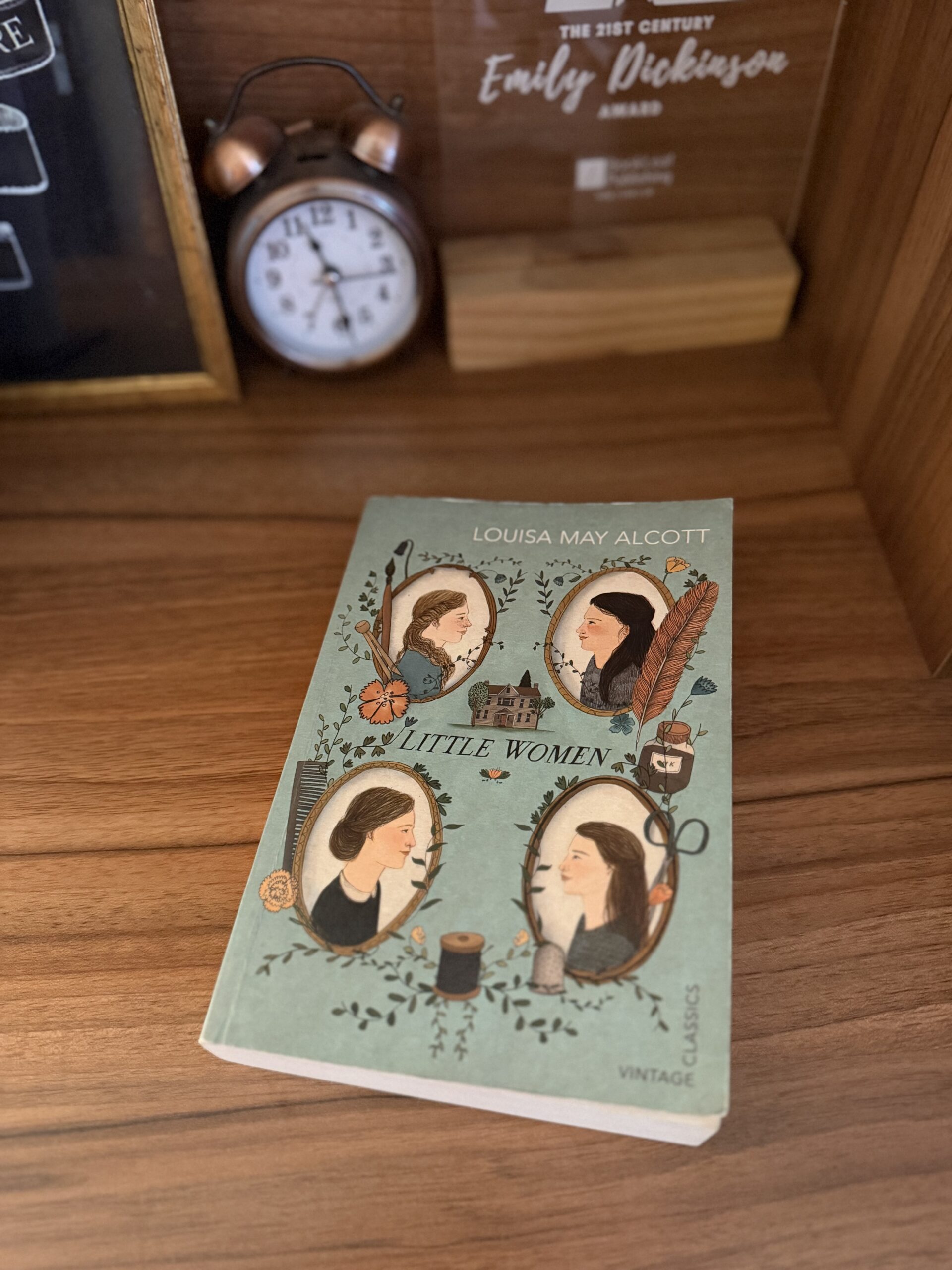

Drawing heavily from Alcott’s own life, Little Women is an enduring American novel, set during the tumultuous American Civil War. On one level, it appears to be a picture-perfect tale of the March sisters navigating their lives in a gentle domestic society. On the other hand, it is a coming-of-age novel that probes the inner recesses of characters torn apart by societal expectations.

The first time I picked up this book was at an airport. At once, the language struck me as unlike any American novel I had read before. It reminded me of those school-time fables that kids are often hooked on to: simple in tone and didactic in intent. But at an age that craves depth and layers, the book didn’t quite capture the vibe at first. Until I picked it again from the shelf, and the ease of its storytelling slowly drew me in. What the book unfolded is more than a string of moral lessons, but a layered commentary on the values and aspirations of middle-class American households in the 19th century.

It is certain traits of the characters seem too idealistic, leaving one to question whether the personalities are fully three-dimensional. Yet once you let go of that initial perception, you’d realise that there’s more to each character than meets the eye. I was so intrigued by the ordinariness of the story that I felt compelled to discover if the novel is inspired by Alcott’s own life — and it is. While the heroine Jo finds a parallel in Alcott’s literary ambitions, Meg corresponds to Alcott’s elder sister, Anna, who found her own “John Brooke” in life through John Bridge Pratt.

The March sisters— Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy- hold their own notions of a “happy life”, and it is through the character of their mother, Mrs. March (lovingly called Marmee), that they realise that life is not all sunshine and rainbows, but also unexpected turns that are necessary to find true meaning. Alcott explored the lives of the March sisters across two novels: the first part, published as “Little Women” in the year 1868, and the second part, published as “Good Wives” in 1869. With their father off to war serving for the Union Army, the girls are brought up under Marmee’s supervision, who always encourages them to be the best version of themselves. It is under her unwavering guidance that they come of age and transform into little women.

The book is a vivid portrayal of the everyday lives of a poor yet loving family. It also explores the relationship of the sisters with Laurie (the well-to-do neighbour), who lives with his grandfather, Mr. Laurence. His bond with Jo March, rooted in shared camaraderie and mischief, is the most memorable relationship explored in the novel. He often shapes the sisters’ lives through new adventures that range from naughty pranks to heartfelt acts of kindness.

Meg March, the eldest of the four sisters, lives her life wishing for pretty and extravagant things in life. A comfortable home, a loving partner, pretty dresses to wear, and beautiful artefacts to own. At an age when she’s expected to seek a partner and settle down, she frequents parties hosted by affluent families in America. Yet it is Laurie who opens her eyes with his disarming honesty, once remarking at a party that she doesn’t quite look like herself with her borrowed finery. Initially tempted by material pursuits, Meg soon realises that there’s more to life — especially when she becomes fond of Laurie’s tutor, John Brooke. In the novel, Meg embodies the yearning for stability and conventional happiness associated with a settled home and loving family.

Jo March, second to Meg, thrives in defying the societal norms and proving a woman’s worth equal to that of her male counterparts. Serving as the author’s mouthpiece, Jo is consumed by a love for literature and writing at a time when women were largely bereft of economic opportunities and the right to independence. She’s headstrong and rebellious, and is deeply in love with her family. Throughout the novel, we find her scribbling stories in her attic, staging plays with her sisters, and guarding her hard-earned independence. Her deepest desire is to become a published author, a dream that finds fulfilment in Alcott’s sequel, “Good Wives”. Her boyish energy finds a match in Laurie, who, at the height of their friendship, challenges her, teases her, and appreciates her love of reading. Jo’s love for literature goes beyond writing, and this manifests itself through her_ Pickwick Club_, which is one of her amateur attempts at storytelling. Thanks to her sisters, she always had a way of exploring her art with their help. Throughout the novel, readers are gently led to anticipate an eventual union between Laurie and Jo. Yet, the duo’s sibling-like friendship and Jo’s unrelenting pursuit of a literary career ultimately override any possibility of a consequential marriage, much to the readers’ surprise.

The third of the March sisters, Beth, is portrayed as shy, frail, and perhaps the most virtuous of them all. Her compassion is evident in the way she tenderly cares for her dolls, in her selfless nursing of the scarlet fever–stricken family during her mother’s absence, and in the reverential companionship she develops with Mr. Laurence, the senior neighbour and Laurie’s grandfather. Music offers Beth both solace and self-expression. Too timid to begin a conversation, she communicates through the piano, breaking the ice with Mr. Laurence and, in doing so, drawing him closer to the March household. In her quiet way, she becomes the moral anchor of the family—the gentlest manifestation of contentment without yearning for riches, fame, or worldly pleasures. Beth is a reminder that a life lived simply can be both authentic and profound.

The third of the March sisters, Beth, is portrayed as shy, frail, and perhaps the most virtuous of all the March sisters. Her compassion is evident in the way she caresses her dolls, for the Scarlett-fever-stricken family that she selflessly tends to during her mother’s absence, and even in the way she develops a reverential companionship with Mr. Laurence, the senior neighbour and Laurie’s grandfather. Music provides her with warmth and the truest form of expression. Being too timid to start a conversation, it is through her music that she breaks the ice with Mr. Laurence, and brings the entire March household together every evening. She’s the most gentle manifestation of being content with one’s own life, without yearning for riches, fame, and worldly pleasures. She’s a constant reminder that a life lived simply is often authentic and raw.

The youngest, Amy, is second only to Jo in terms of having aspirations. She’s fiery and knows what she wants — a life of refinement, external beauty, and the possession of precious material things. With a natural talent for painting, she doesn’t want to settle for anything dull or colourless. Yet, she lacks Beth’s humility, Meg’s seriousness, and a disciplined approach to one’s passion like Jo. Amy’s frivolousness and quick temper often lead her to impulsive outbursts, most prominently exemplified when she destroyed Jo’s much treasured manuscript in a fit of spite and malice. She’s a prime example of how things can go south when unchecked by humility and self-awareness. However, despite her initial fractious behaviour, Amy serves as the epitome of transformation and reform. She develops a strong bond with Aunt March in the latter part of the novel and finds true meaning in Christian gratitude and learning. Though she starts as immature, as expected of any twelve-year-old adolescent girl, she is also the most reflective and resolute of all sisters.

If we were to put Laurie at any position with respect to the March sisters, he’d undeniably fit as the fifth March sibling. Unlike the sisters, Laurie comes from a well-to-do household and lives under the stern guardianship of his grandfather, Mr. Laurence. Being an orphan, he has lived most of his life aloof and only finds refuge when he comes in contact with the March household. The arc of Laurie’s relationship with Jo took a different turn when Alcott snapped the thread of predictability and didn’t explore a romantic relationship between the two. Despite that, Laurie remains to catalyst behind their journey to adulthood.

If you’re fond of classics, you’ll definitely find a rescue in the easy-flowing words of the novels. I have read many Jane Austen novels before, and my conviction was that probably Alcott is America’s own Austen. But on deeper analysis, I understood that while Austen’s works breathe wit, irony, and satire on the larger social conventions of her time, Alcott was mostly focusing on family values, growth, and morality. Moreover, Austen’s heroines are mostly seen navigating rigid social hierarchies of the English gentry for marriage. On the other hand, Alcott emphasises that women don’t necessarily need to consider matrimony as the only resolution. They can still focus on family values and live a fulfilling life through art, work, humility, and service. Hence, while Alcott continues Austen’s legacy, she also deviates from it — thus sowing a unique American hybrid in a literary field long dominated by British blooms.