Understanding Life Through Anna Karenina

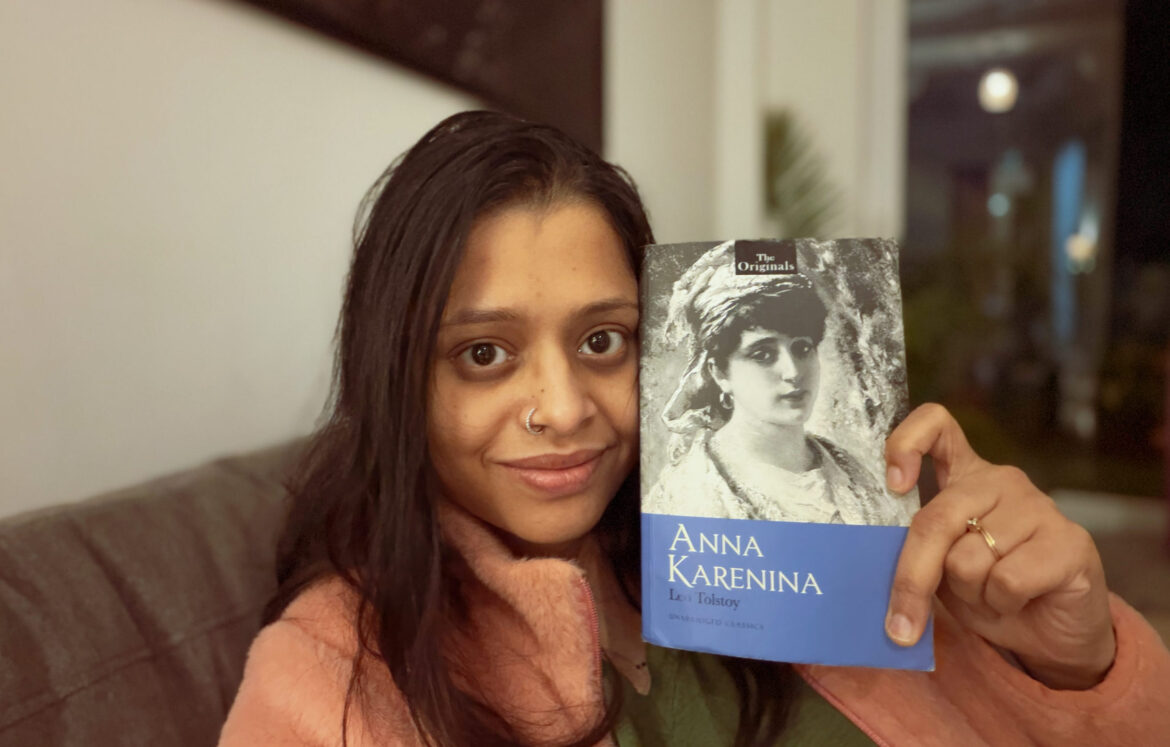

- by Namrata Das Adhikary

- November 29, 2025

- 0

- 114

Around five years ago, I saw the shiny blue cover of Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina peeking at me from a bookstore shelf. At first, I didn’t dare. But after a few minutes of intense bargain, I finally gave in. I bought the well-renowned Russian novel, only to add yet another ignored piece of literature to my home library. The sheer volume, coupled with the general awareness around how painstakingly elaborate any Russian novel tends to be, kept me from taking on a reading challenge for years. During my annual cleaning sprees, I’d dust its cover gently, as if promising, someday.

Until recently, when, after reading Gogol’s “The Overcoat”, something in me shifted. It was just another lazy and uneventful morning, when I thought, ‘Why not?’. To my surprise, I read the first thirty pages with such attentiveness. The rest followed as effortlessly as a knife gliding through melted butter. Tolstoy, I realised, was a genius.

I won’t attempt to unpack the novel’s vast, gargantuan plot that offers a panoramic and layered view of Russian life. Instead, I’d like to dwell on a few pointed insights that I gathered from it — about love, passion, infidelity, occupation, and faith, among other things.

Anna Karenina isn’t merely a tale of a “fallen woman” who dared to be a non-conformist. It’s a tapestry that weaves together the imperfect lives of Vronsky, Levin, Kitty, Darya, Oblonsky, and several characters who orbit them. What I love about the novel is despite the vastness, it’s a narrative that’s derived from the everyday happenings, dissecting thoughts as they arise, discussing events as they occur, and unfolding lives with such intimacy that it almost feels intrusive. And yet, beyond its realism, there are some key observations I’ve gathered from the text, reflections that lingered with me even after I turned the final page.

The Unequal Weight of Sin

While Oblonsky could get away with the compromise of a timid and a submissive wife following his repetitive affairs, Anna was boycotted by her husband and the society for seeking love beyond her loveless marriage. Dolly is expected to adjust and compromise her happiness for the sake of children and society, but for Anna, the world turns their back on her. Through these parallel portrayals of infidelity, Tolstoy exposed the hypocrisy embedded in a patriarchal morality. He lays bare the double standards with brutal reality, so much that the readers can almost feel the tangible burden of being a woman in an unjust society. In both cases, it is the woman who bears the punishment for the man’s sin.

Labour, Land, and the Illusion of Progress

Being one of the central backdrops of the novel, Tolstoy paints a vivid picture of Russia amid changing societal structures, particularly through the character of Levin. The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 granted freedom to peasants whose rights had previously been severely restricted under landowners. Their liberation sparked widespread discussion about existing labour laws and highlighted the inner turmoil between holding on to traditional methods and values versus modernising the agrarian system. I felt that Levin genuinely supported the idea of emancipation, but he was deeply disheartened by how little it changed the peasants’ lives in practice. The new land systems, too, were inefficient, which led to frustration. Yes, he did reject the old practices, but wasn’t completely in favour of the emerging capitalist mindset either. He longed for a more cooperative relationship between the peasants and the landowners and believed that one must participate in endless and honest labour one can truly earn the fruits of their work.

Desire, Despair, and the Death of Self

Any character fighting the demons of their mind is one of my favourite genres, and honestly, I never thought that The Bell Jar could have a competition. Tolstoy sure did a fantastic job in translating the disturbing mental condition of Anna, who, being deeply disturbed by Vronsky and the hypocritical society alike, had to resort to suicide. Unpopular opinion, but her inner monologues are more powerfully portrayed than in the American counterpart.

The Human Struggle to Make Sense of Life

If there’s any character who has truly embodied the human struggle to understand life’s larger truths, it is Levin. Through him, Tolstoy explores the restless scepticism that exists in all of us: that quiet, persistent questioning of what society tells us to believe. Throughout the novel, we find him wrestling with faith; questioning what society imposes on us when it comes to religious and moral understanding. Neither did he fear questioning the unknown, nor did he close himself to the possibility of experiencing a change of heart, which he eventually did.

A Title Too Small for Its World

I also feel that the title “Anna Karenina” doesn’t fit quite right, as I think the book is as much Vronsky’s as it is Levin’s, Kitty’s, Dolly’s, Oblonsky’s — or even of the entire Russian society. To call it only Anna’s story makes the prospect of the novel quite limiting. While Anna’s plight exposes the orthodox notions of a woman’s position in society, Oblonsky’s marital affair reminds us how being a man often comes easy. On the other hand, Alexei Karenin’s conflict with himself following the discovery of Anna’s affair highlights the deep moral paralysis that comes with pride and reputation. He is torn between the appearance of virtue and the genuine act of forgiveness- a struggle that reflects the hypocrisy of the very society he tries to uphold. In him, Tolstoy paints the tragedy of a man imprisoned by his own ideals, just as Anna is destroyed by hers.

The Pain and Power of Childbirth

Childbirth isn’t a piece of cake, and Tolstoy makes that abundantly clear. It’s explored not just once but through multiple women in the novel. From Dolly, who silently contemplates the monotony and exhaustion that follow motherhood, to Anna, who dreams of losing her life in childbirth (and nearly does, struck by fever and delirium soon after); each portrayal reveals a different shade of a woman’s vulnerability. Even Kitty’s journey to motherhood is described with painstaking detail. The anxious waiting, the presence of the nurse, and the care and attention surrounding her before and after the birth. Through these scenes, Tolstoy strips away the romantic veil around motherhood and shows it being painful, transformative, and deeply human.

The Quiet Triumph of Steady Love

Wild love might suffice one’s innate desire and passion, but it is certainly not enough for leading a reputable life as a couple. When contrasted with Levin and Kitty’s stable marriage, Vronsky and Anna’s relationship appears more hinged on fiery love and romance, one that consumes rather than sustains. It leads both the hero and the heroine nowhere in life. On the other hand, marital bliss and understanding fill Levin’s life, who finds peace not in passion, but in companionship. His marriage with Kitty is rooted in quiet affection, honesty, and shared purpose. Through this contrast, Tolstoy seems to suggest that the truest form of love is not the one that dazzles, but the one that endures.

Honestly, when I turned the last page of the book, the characters reverberated in my mind for quite some time. I wonder why Russian classics aren’t as popular as their British counterparts, ’cause the former not only beat the English in terms of the depth of their characters by touching upon several dimensions but also rank higher in the vastness with which society is explored.